Shahieda Hudson felt a combination of luck and loss from this month's destructive tornado.

Hudson lives in St. Louis' Wells Goodfellow neighborhood, which experienced uneven damage after an EF3 tornado ripped through parts of north St. Louis.

The tornado poked holes in brand-new siding on Hudson's house, but she didn't lose power for a significant amount of time. Across the street, though, the tornado broke Hudson's neighbors' windows and cut off power – spoiling food and perhaps causing permanent damage to anything plugged into a wall. And the storm devastated the home of Hudson's aunt and uncle, as well as one of their cars.

Hudson and her relatives plan to apply for Federal Emergency Management Agency individual aid, which could provide critical funds for tornado-related property damage, medical costs, transportation needs or temporary housing arrangements.

"The FEMA aid was an expectation that we all had in the event that we needed help, in the event that there was a major disaster, that the taxes that we paid would be there for us in an emergency," Hudson said.

But Hudson, her family and her neighbors can't send in their application until President Donald Trump signs Gov. Mike Kehoe's major disaster declaration request, which is awaiting action along with scores of similar pleas in other states. The wait for that critical aid comes amid widespread concerns about whether the Trump administration can handle natural disasters around the country.

While the wait for aid isn't unusual or unprecedented, Hudson said the federal vacuum forced volunteers and nongovernmental groups to bear the burden of the tornado's initial recovery.

"Until then, you're left in the elements," Hudson said. "No clothes. No car. No transportation. No medical assistance. No transportation for follow-up visits. But you're still expected to show up to work. You're still expected to show up to school and not be able to take care of your basic needs."

How federal aid can help

FEMA aid is split into two broad categories: individual help and public assistance. The public aid goes to state and local governments to, among other expenses, pay for worker overtime or to repair public buildings. Kehoe is expected to ask Trump to approve public assistance aid after FEMA officials finish preliminary damage assessments from the tornado.

If Trump approves Kehoe's request for individual aid, which the GOP governor sent earlier this week, individuals can apply to FEMA for a number of different types of help, including:

- Rental assistance for people who were displaced from their homes.

- Reimbursements for people staying at hotels or motels.

- Home repair or home replacement.

- Child care-related expenses.

- Medical or dental bills stemming from the tornado.

- Personal property replacement, such as for home furnishings or computers.

- Transportation repair or replacement if a vehicle was damaged or destroyed.

While FEMA is not meant to make disaster victims financially whole or be a substitute for homeowners insurance, it can provide much more money to individual recovery efforts than any state or local program. For fiscal 2025, the maximum FEMA payout is $43,600 for housing assistance and $43,600 for other needs.

"The FEMA aid is intended to make up for a shortfall that still exists after those insurance protections and sort of normal order benefits have already been dispersed," said Evan Mix, a research scientist at the University of Washington who monitors responses to natural disasters.

The rental assistance in particular could be a huge help for Kelly Wichmann, a graduate student who owns a condo in St. Louis' Debaliviere Place neighborhood.

Wichmann's condo suffered catastrophic damage, both during the May 16 tornado and afterward. The initial storm blew the roof off her building. and a subsequent rainstorm later in the week caused extensive water damage in her kitchen.

While Wichmann's insurance policies will likely go a long way toward repair efforts, she said that her building project manager estimated that it could be at minimum a year, possibly two years, before she can move back. And while Wichmann, her partner and their dog are staying with friends for now, her insurance policies will only cover roughly eight months for an apartment.

Because Wichmann can't apply for FEMA aid yet, she said an already stressful situation is even more anxiety inducing.

"There's literally so many unknowns in this entire process, and so every day counts, especially in the community at large," Wichmann said. "There's so many people facing these uncertainties, so many businesses that will probably go under from this impact – because aid hasn't been allocated quickly."

The waiting game

Presidents have the ultimate decision-making power over signing or rejecting a major disaster declaration. And while the timeline varies depending on the situation, historically it's taken about six to eight weeks between when a disaster occurs and a president approving aid.

FEMA officials were able to wrap up their review for individual assistance last week for the May 16 tornado, prompting Kehoe to submit his request to Trump on Sunday.

The timeline for approval can be shorter, such as when President Joe Biden approved a 2022 declaration for St. Louis-area flooding — and when Biden backed a request from Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear two days after a deadly 2021 tornado.

"FEMA has been criticized for much of its existence for not being nimble enough in response to these events, and that's sort of a symptom of bureaucratic agencies in general and the way they operate," Mix said. "It's not unique to FEMA, and it's certainly not unique to this incident."

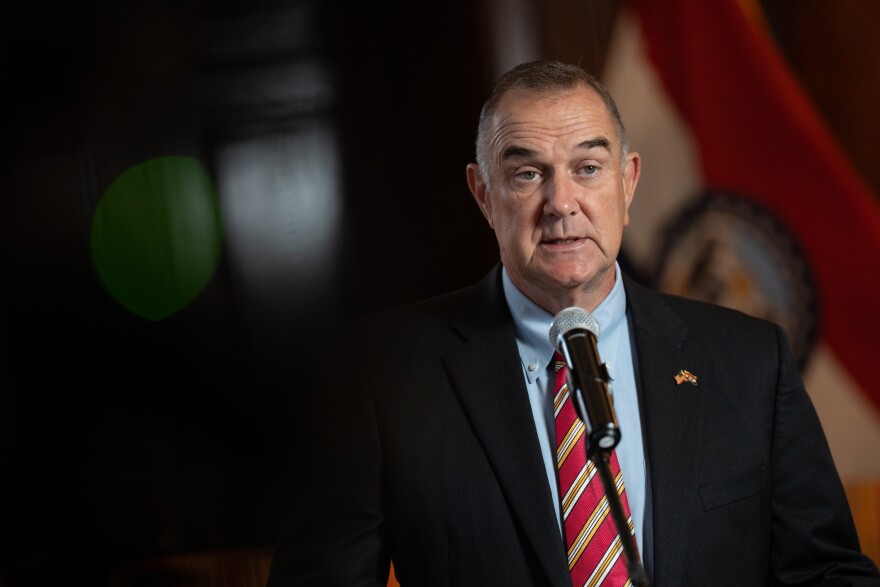

Kehoe acknowledged this week that he doesn't expect an instantaneous response to his major disaster declaration request.

"So it unfortunately takes a little longer than as a small-business guy I like sometimes," Kehoe said. "But we're grateful for the response we've gotten so far, and we'll keep pushing."

Missouri's congressional delegation is urging Trump to act quickly. For Congressman Wesley Bell, D-St. Louis County, speed is important since some of the tornado victims are sleeping in tents in front of their homes.

"We have to have a unified front to pressure the administration to do the right thing," he said.

Missouri U.S. Sens. Josh Hawley and Eric Schmitt, both Republicans, have also been active in communicating with the Trump administration about tornado relief. Schmitt said he spoke with Trump and White House officials about storm relief. And Hawley received commitments at recent committee hearings from Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and Small Business Association Administrator Kelly Loeffler to get aid to St. Louisans.

"FEMA has a lot of resources, and we want to see all of them deployed here," Hawley said at a May 19 press conference. "And we want to see assistance come in full to this area. So I'm going to be a dog on a bone with that."

The Trump effect

But both elected officials and experts in disaster response have widespread concerns about how the Trump administration has handled federal relief since he returned to the White House.

Trump has rejected disaster declaration requests in places like Washington state, West Virginia and, initially, Arkansas.

Lynn Budd, director of the Wyoming Office of Homeland Security and the president of the National Emergency Management Association, said, "it's been clearly messaged that there is a desire for the states to take on more of the responsibility for disasters."

"I think it's going to take some time. We can't do it today, and there's different capabilities of different states," Budd said. "Some people already have their own state programs that cover individual assistance and public assistance on a state level. Many states do not. So I think there needs to be some time for states to build that capability, and there still needs to be some skin in the game for the federal government. Because when it comes down to it, this is a team game here."

Schmitt and Bell said they aren't expecting Trump to reject Missouri's major disaster declaration request, especially since the president approved Kehoe's aid plea for a series of March and April storms. Kehoe also said he isn't worried that Trump will reject his request.

"I feel good in talking to the president and to our two senators that we'll get some good news in those pretty soon," Kehoe said on May 22.

Several news reports found that more than 2,000 full-time FEMA employees have left the agency since Trump returned to office. Budd said a FEMA with a smaller staff may have a tougher time knocking on doors to get people to sign up for aid, while others added it's an open question on whether those job reductions will affect the delivery of aid to individuals.

"I would be very surprised if cutting staff at that level did not impact service delivery in some way," Mix said. "Everything from the speed of these review processes to the actual provision of aid."

Asked about whether the FEMA jobs cuts will affect federal recovery efforts if Trump backs Kehoe's disaster declaration, Schmitt said that adding more employees during Biden's administration didn't necessarily lead to improved service delivery.

Schmitt also said Trump is undertaking efforts to overhaul FEMA, alluding to how the president established a commission looking at different ways to respond to disasters.

"My focus is making sure that it's responsive to this and for Missourians," Schmitt said. "But I do think a longer-term conversation is, how do we reform FEMA to be better? And this isn't a partisan thing. I think this is something that I talk to colleagues in California who are Democrats in the Senate. They're frustrated with it, so hopefully it's something we can kind of come together on."

Filling the void

As St. Louisans await Trump's decision on Kehoe's disaster request, other groups are stepping up to fill in the federal void. That includes volunteers and grassroots organizations, as religious institutions and private businesses.

For Hudson, the immediate response to the tornado should provide some lessons to local and state political leaders. Had city leaders invested more time and money into emergency preparedness, Hudson said it may not have fallen on nongovernmental groups to handle much of the short-term storm response.

The Missouri National Guard arrived in St. Louis this week to help remove storm debris, while city officials are continuing to organize relief efforts.

And while Hudson stressed that the federal government can help hasten recovery efforts, she added that residents need to be vigilant that it doesn't lead to unintended consequences – such as creating situations where long-term residents with fixed incomes are ultimately taxed out of their homes.

"It will be left up to those of us who can still afford to be in this area to never forget and to remind them that we were alive when the response by the city and by the state left the neighbors and the community members, left the students left the elderly to fend for themselves for a week while they passed the buck off to NGOs, churches, private businesses and large corporations," Hudson said.

St. Louis Public Radio's Will Bauer provided information for this story.

Copyright 2025 St. Louis Public Radio