Angie Rodgers sits in a small, air-conditioned shed plopped down in the middle of Sloanville Drive outside Sikeston, Missouri. She works on her computer surrounded by piles of personal hygiene kits, lost items and boxes from the local foodbank.

"So, the command post is a makeshift area," Rodgers said. "We have put a shower trailer that has been donated for our use by DAEOC (Delta Area Economic Opportunity Corporation)… We have a washer and dryer for the residents. We have porta potties."

It's June 13 — just three weeks since an EF3 tornado swept through several areas of the state, including Scott County, and left the community of Sloanville in pieces.

Rodgers, the executive director of the Scott County 911 Emergency Service Board, said they've been out in the command post nearly every day since trying to help residents of this isolated, tight-knit community get "back to a self-sufficient state."

"It was an absolute war zone out here. It was mass chaos."

Rodgers said that May 16 started off as a normal day – she was working in the office and there was a possibility for tornados in the area.

"But out of nowhere, they just kind of spun up, and here they were. It went from nothing to chaos within about 2.3 seconds," Rodgers said.

She said, at first, she didn't know the extent of the damage, but as she headed toward Sloanville, the roads became unpassable, and she got word that this most recent tornado had taken lives.

"There are no weather sirens out here, anything like that, being in the county, in such a rural area," Rodgers said. "So, if they were outside, which we did have several people outside, they didn't have a warning until they could see it, and then it was there and it was too late."

She later learned that an EF3 tornado had ripped through the area – impacting several small, rural communities on the outskirts of Sikeston: Sloanville, Woodhaven and Sandywood.

She said these areas were uniquely positioned for damage. In Sloanville, in particular, families live in what Rodgers called "colonies," which are essentially a piece of land where numerous family members lived — some in houses, others in mobile homes and trailers.

"It doesn't take much to destroy a camper, but it also takes a lot to rebuild it. So, we're looking at rebuilding things that really weren't meant to be rebuilt. Or the mobile homes that are out here — they're not brand new, they're not the fancy ones," Rodgers said. "They were building their legacy, and that's what their legacy was."

Rodgers said the first few hours and days were focused on rescue and sheltering people, but then came the next challenge: feeding those who'd lost everything.

"Our initial main goal was to get food out here to people that was already pre-made."

Rodgers says luckily some local churches and non-profits, such as the Red Cross, Old Bethel Baptist Church and Hope International, began providing lunches and dinners for residents. And the Southeast Missouri Food Bank began sending water and boxes of shelf stable food.

But hot meal service could only last so long, and Rodgers said shelf-stable food was great, but residents had nowhere to cook it.

"We still have at least two or three refrigerators that have not been found," Rodgers said. "Their stoves are gone. Their everything is gone. They have no pots, they have no pans, they have no running water. It's literally in crumbles around them."

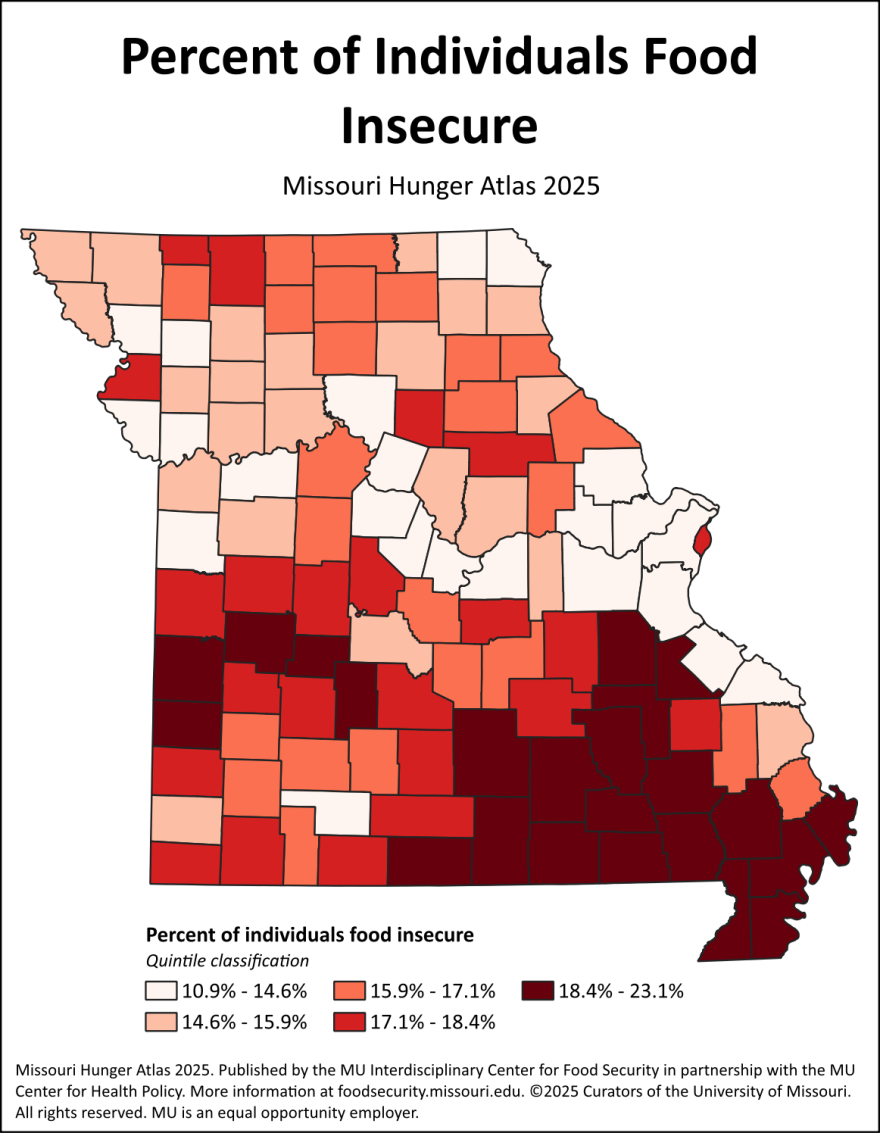

Heather Collier is the donor relations and communications manager for the Southeast Missouri Food Bank, which covers 16 largely rural counties in the southeastern part of the state. She said even before this disaster, this part of the state struggled with food insecurity.

On average, the food bank serves 80,000 people a month across 140 partner agencies.

"A lot of people in our community are living paycheck to paycheck, so one unexpected car repair or health care costs, anything that comes up can really blow up their monthly budget," Collier said.

She added that for many of the people she's spoken to who've been impacted by the tornadoes this spring, it's not just the loss of everyday groceries. It's also the loss of significant amounts of protein that they had stored in their freezers, either from deer hunting season or from purchasing half a cow.

"Disaster, especially a tornado, can take away everything. It takes a long time to recover," Collier said. "It's not going in once and dropping some food off and saying, 'Here you go, we've helped you.' It's really working with other agencies to do a wrap around and making sure that these people have the resources they need."

"Rebuilding from a tornado, it's a long process."

There are federal programs, such as the Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or D-SNAP, that are supposed to help with this longer-term recovery — and the restocking of a pantry.

D-SNAP is a program operated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture that a state can apply for once a disaster is declared by the President.

"D-SNAP is something that's available to other families and people … who have gone through the disaster, who are not participating in SNAP," said Salaam Bhatti, the SNAP director for the Food Research and Action Center, a national advocacy group. "This provides them with one month worth of SNAP benefits to help replenish their food stock."

With D-SNAP, those living in an impacted zip code would be eligible for temporary food assistance, and those already receiving SNAP benefits could get replacements for what is lost.

According to the Food Research and Action Center's "Guide to Federal Nutrition Programs During Disasters," states should consider applying for D-SNAP when there are "large numbers of affected people who would not be helped under the eligibility criteria and benefit replacement processes of regular SNAP."

But since St. Louis-area flooding in 2017, Missouri hasn't utilized anything other than the more basic replacement waiver, which allows people to report lost food beyond the normal 10-day limit following a natural disaster.

"Each event is assessed individually, taking into account the level of damage and its impact on households," a Missouri Department of Social Services employee wrote in an email. "There are specific criteria that must be fulfilled before requesting either the replacement waiver or D-SNAP."

Missouri has applied for and been granted the replacement waiver numerous times in 2025, 2024, 2023, 2022 and 2021 for disasters, such as severe storms and tornadoes.

But many neighboring states have utilized the full D-SNAP program after similar disasters: Tennessee, Oklahoma and Iowa all operated D-SNAP in 2024, Arkansas utilized it in both 2024 and 2025 and Kentucky has offered D-SNAP in response to two different natural disasters this year.

The DSS spokesperson continued, "in times of natural disasters, SNAP outreach partners typically provide assistance."

According to those involved in the Sloanville rescue, the local SNAP office was available to help people after the tornado, and the Southeast Missouri Food Bank was there to do emergency food distribution.

But local SNAP offices and food banks are stretched thin, as food insecurity has never fallen back down to pre-pandemic levels, and the SEMO food bank said they've responded to "nine or ten" tornados. So, if the state applied for the extra benefits, it could make a difference.

"I lost count of the number of tornadoes we had," Heather Collier with the SEMO food bank said. "I know I took shelter three times, so we had a lot of communities affected. I think we've done nine or 10 emergency mobile distributions in communities that were most severely impacted by those tornadoes."

And it could get harder for states to offer such benefits in the future, as the Trump administration seeks to transition much of the administrative cost and burden of regular SNAP to the states.

The recently passed Federal Reconciliation Bill, or "One Big Beautiful Bill Act," will make the state responsible for more of the costs associated with SNAP.

Gina Aitch is a policy analyst with the Missouri Budget Project, a nonprofit that analyzes the state budget and tax policy. She said, starting in fiscal year 2028, Missouri will be required to cover 75% of the administrative costs of the SNAP program, instead of the current 50%.

Additionally, once the bill goes into effect, Missouri will be required to cover part of the costs of the benefits provided to individual Missourians. Currently, the federal government provides 100% of these benefits.

This amount will be dependent on a state's "payment error rate," which measures how accurately the state has been at determining people's eligibility. This rate is determined by Food and Nutrition Service of the USDA.

"It's not uncommon for states to have least some errors and most errors are unintentional," Aitch said. "But now going forward, instead of the federal government paying 100% of benefits, states will now have to pay a part of the cost of benefits based on their payment error rates."

The Missouri Budget Project estimates that these changes will likely cost the state between $160 and 235 million dollars, depending on what their payment error rate is when determinations are made.

Salaam Bhatti, with the Food Research and Action Centers, said these additional costs could make it hard for the state to continue SNAP, as well as D-SNAP.

"State staff agencies are underfunded and understaffed already," Bhatti said. "This would result in a decreased capacity at the state level …You'll have that impacting rollout for D-SNAP. You may even have an impact where the state does not request D-SNAP. So, we could be on the brink of a disaster for D-SNAP."

Bhatti added that current social programs are vital to meeting food needs in Missouri. About 1 in 10 Missourians is enrolled in SNAP. But this could change. As the state takes on more of the program costs, more money will be needed to fund it. Otherwise, SNAP benefits could be cut or eligibility restricted.

"And people should know that food banks, food pantries, churches, cannot make up the gap that would be left if SNAP is gone," Bhatti said.

For the audio transcript, click here.

Copyright 2025 KBIA