Changes and cuts to Medicaid in the so-called "big beautiful bill" that President Donald Trump signed into law earlier this month have rural hospitals and health care advocates concerned.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the legislation will reduce Medicaid spending by nearly $1 trillion over the next decade, leading to more than 11 million people losing health insurance during the same time period.

Larry Levitt, the executive vice president for health care policy at health care research nonprofit KFF, said during a recent webinar that those numbers will likely come down some due to last-minute changes. Still, he said, the impacts will still be "staggering."

"This represents the biggest rollback in federal support for health coverage ever," Levitt said.

About $155 billion of the $1 trillion cuts will impact rural areas, according to KFF. The bill's defenders point to a $50 billion Rural Health Transformation Fund created by the legislation. That fund was beefed up in the Senate version of the bill to assuage concerns from rural lawmakers, particularly about potential closures to rural hospitals.

Still, some health care researchers and hospital representatives aren't confident that the investment will offset the cuts, especially with an unclear system for awarding funds and a bleak landscape for rural hospitals that existed long before the bill was signed into law.

"There's still a lot to figure out with that Rural Health Transformation Fund," Cindy Samuelson, a spokesperson for the Kansas Hospital Association, said. "Don't get me wrong – I think Kansas hospitals are appreciative of any support they can get, but this would only be temporary and it's not yet determined who would benefit."

The fund will be administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and requires states to submit a "rural health transformation plan" by the end of this year. The first $25 billion from the fund will be equally distributed between all states who complete a successful application. The remaining $25 billion will be distributed to states as decided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The fund will last for five years, with $10 billion to be doled out annually.

Rich Rasmussen, the president and CEO of the Oklahoma Hospital Association, called the fund "a drop in the bucket."

"It does not replace at all the cuts that hospitals are experiencing," he said.

Struggles for rural hospitals are nothing new

It remains unclear how many rural hospitals will be impacted by the bill's Medicaid cuts. In a list compiled by Democratic Senators, a total of 338 rural hospitals across the country were identified as at risk of closure. A separate study from the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform (CHQPR), which advocates for affordable health care, estimated that 760 hospitals across the country were at risk of closure, with 314 of those facing an imminent threat.

Rural hospitals have been struggling financially and facing closure far before the passage of Trump's tax and spending bill. A study from the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research found that 154 rural hospitals have either closed entirely or eliminated inpatient services since 2010. That includes 21 rural hospitals in Texas, 10 hospitals in both Missouri and Oklahoma and nine hospitals in Kansas.

An additional 41 hospitals have shifted to the Rural Emergency Hospital model, which went into effect in 2023. Established to prevent health care deserts in rural areas, the program allows hospitals to eliminate inpatient services while still providing 24-hour emergency care and observation.

In the Midwest and Great Plains, Kansas and Oklahoma face the largest immediate threat of additional hospital closures. The CHQPR study estimated that 29% of rural hospitals in both states are at an immediate risk of closing in the next three years.

Kansas' rural hospital system is one of the most endangered in the country. In 2022, the median operating margin for Kansas hospitals was negative 12.7% – far below the national average margin of negative 3.8%. Nearly all of the state's rural hospitals operate at a loss, and about 15% of all hospital patients are on Medicaid.

Samuelson said it's hard to pinpoint one reason for the struggles the state faces. Medicaid only reimburses about 65 cents for every dollar spent on Medicaid care. The state is one of 10 that has not adopted the optional Medicaid expansion package under the Affordable Care Act, which makes more adults eligible for coverage. Nearly a quarter of the "bad debt" carried by Kansas hospitals – the portion of patient bills deemed uncollectable – is from people who have insurance but can't pay their out-of-pocket costs.

"Nationwide inflation has increased all the costs, but the stagnant reimbursement from our payers has not changed," she said. "Plus, the fact that we're a state that has some workforce challenges recruiting and retaining qualified staff… These things are coupled all together to really cause some challenges in the state of Kansas."

In Oklahoma, it's a similar tale – though Rasmussen said the state made significant progress in recent years that he worries will be rolled back under the new law. Oklahomans voted in 2020 to expand Medicaid, which helped close the coverage gap.

"We're looking at a very, very different environment going forward," Rasmussen said.

Rasmussen said he worries about the broader impacts that the loss of these services will have on rural communities.

"You'll have more flight to urban areas," he said. "When we restrict the services even further, you'll have seniors and other people say, 'you know what, it's time to close the farm. It's time to close my business. I'm going to relocate.' And that would be a travesty, all because people lose access to something that is a true need."

Provisions most concerning to rural hospitals

Rural health advocates and hospital associations are especially concerned by two provisions in the bill: A phasedown of provider tax rates, and a new cap on state directed payments. Both are tools that states use to receive more federal matching funds.

"The more money that a state pushes up to the feds, the more money the feds bring back down," explained Jed Hansen, the director of the Nebraska Rural Health Association.

All states except for Alaska use some form of provider taxes or fees to help finance the state share of Medicaid costs. The taxes or fees are assessed on an entire class of providers, like hospitals or nursing homes. States then spend the money received from the taxes or fees to fund their share of the Medicaid spending, thereby increasing the amount of money matched by the federal government.

Critics, such as the conservative health policy think tank Paragon Institute, have referred to provider taxes as "legalized money laundering."

Under federal rules, the tax or fee is considered automatically compliant with certain provisions if it is at or below 6% of the provider's net revenue from treating patients. In practice, the 6% limit acts as a cap on provider taxes.

The "big beautiful bill" will incrementally phase down that cap to 3.5% starting in 2028. It will also prohibit states from establishing new provider taxes. States that have not expanded Medicaid, like Kansas and Texas, will be exempted from the moratorium on new provider taxes and the phasedown in current rates.

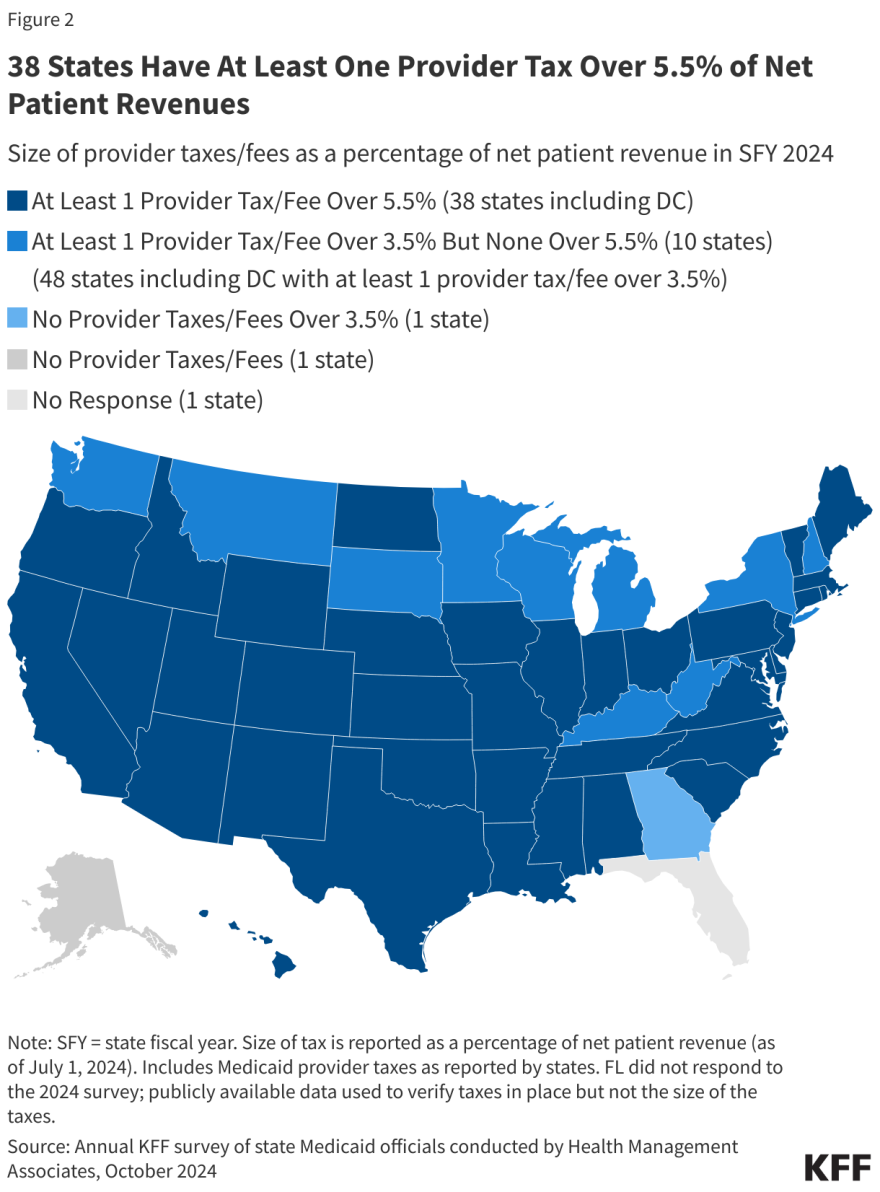

According to KFF, 38 states have at least one provider tax above 5.5%. Rasmussen said all states with rates above 3.5% will "have to make adjustments to their provider fees, which will put pressure on state governments to further cut Medicaid."

"If state governments don't have the resources, they will cut hospitals, they will cut behavioral health therapists, they will cut physicians and other providers," Rasmussen said.

There are similar concerns about the changes made to state directed payments – which are essentially a way for states to instruct managed care organizations to pay hospitals or other health care providers more when they treat Medicaid patients. Currently, most states use rates set by commercial insurers as a benchmark for determining state directed payment rates.

The new provisions will require that any new state directed payments are capped at 100% of Medicare rates, or 110% of Medicare rates in states without Medicaid expansion – both far less than commercial rates. Starting in 2028, states with directed payments above that level will be required to phase down payments by 10% each year to reach the Medicare level cap.

Nebraska's first state directed payment plan for inpatient and outpatient hospital services was approved by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services in June. Hansen said the cap will mean a significant decrease in the amount of money paid out to hospitals under that program.

"We've got this bucket of $950 million, and for the next couple of years, that will remain in place," he said. "If fully implemented, the big beautiful bill will reduce our hospital's directed payments from about $950 million today down to about $150 million a year. That would be roughly 12 years from now."

Other states in the Midwest would see similarly large decreases in payments to hospitals. Health care nonprofit The Commonwealth Fund estimated that Iowa will see a 54% reduction in state directed payments to hospitals under the Medicare rate cap between 2026 and 2034. Michigan is expected to see a 45% decrease over the same time period.

With both of these provisions not scheduled to begin until 2028, there's some hope for hospitals that lobbying and political swings could delay or soften the blow of the changes.

Republican U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, who voted for the legislation but has been outspoken in his support for Medicaid funding, introduced a bill last week that would repeal the provider tax and state directed payments provisions in the new law. That effort is supported by the American Hospital Association.

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest and Great Plains. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.

Copyright 2025 KCUR 89.3