In December 2023, airmen at Langley Air Force Base in Hampton, Virginia, watched as swarms of drones flew above them for 17 nights. The military scrambled fighters and Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) planes, engaged sensors on the ground, and looked for ships off the Atlantic coast.

"We didn't have any luck detecting or further characterizing the threat," said retired Air Force General Glen VanHerck, who at the time was head of North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and Northern Command. "The eyeball was more effective on the ground than any sensors that I had as the commander of NORAD and NORTHCOM to defend our homeland."

He said he asked the White House for the authority to track the signals coming from the drones, but was denied.

"Current policy and law prevents the Department of Defense from collecting signals intelligence in the United States for fear that we would be spying on the American people, or a perception of spying on the American people," he said.

So the military reached out to the Commonwealth of Virginia and police in surrounding cities.

"DOD does not have authority outside the perimeter of the installation. That transfers to the local authorities, and that's one of the challenges that we face," VanHerck said.

Around the country, many local law enforcement agencies are installing equipment to detect Remote ID, a required system on newer commercial drones which acts as a sort of digital license plate.

Jump-started in part by the interest that followed the Langley incident, Virginia is now one of a handful of states that are creating air traffic monitoring systems for unmanned aircraft. It's part of a larger effort to attract drone-related industries to the state.

"The ability to give earlier warning to incursions on Joint Base Langley-Eustis or local law enforcement, fire departments, rescue squads - that's just an added bonus to what we're doing," said Chris Sadler of Virginia's Public Safety Innovation Center.

Over six months in 2023, Sadler's group monitored the skies over Virginia and found 3,000 drone flights. 130 were near critical infrastructure, and more than a quarter were flying above the 400 foot limit set by the FAA.

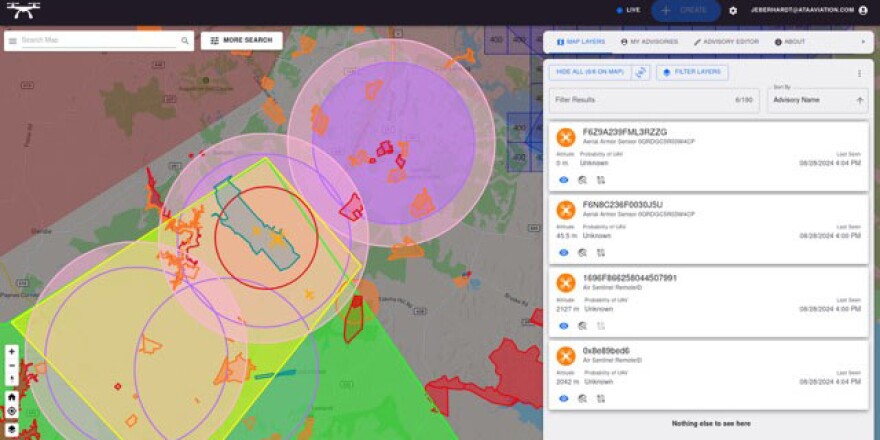

The Virginia Flight Information Exchange started as a statewide map to show drone pilots sensitive areas to avoid - like around airports and military bases. In Stafford County, south of Washington D.C., the partners are getting ready to roll out an array of cameras, acoustic sensors, phased array radars, and other sensors to track the drones themselves, which often don't appear on radar.

"In the areas where we have our full sensor array and our system coverage, we're pretty good. We see almost everything in the sky," said Virginia's contractor, John S. Eberhardt III of ATA Aviation.

The initial project covers only a sliver of Virginia. With more money, the state and local partners plan to install sensors in the Hampton Roads area, which includes Langley and the largest concentration of Naval bases in the world, Eberhardt said.

A December 2024 memo from Air Combatant Command says the Air Force wants to use Virginia's real-time flight data as part of its early warning system. The military also wants to work more closely with local law enforcement, which has the ability to prosecute illegal drone activity.

According to the memo, Langley is also working with NASA, the National Aviation Research and Technology Park (NARTP), the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), and the North Dakota Grand Sky consortium.

The Department of Defense has pilot projects to better track and stop drones that pose a national security threat. The current head of NORAD and NORTHCOM, Air Force General Gregory M. Guillot, told Congress in February that there were more than 350 drone detections at 100 different U.S. military installations last year.

So far, the federal government hasn't offered any money to build or maintain the fledgling system in Virginia, though the tax and spending bill Congress passed in July does have money for drone projects.

"We need a strategy that then leads to authorities, policy, and law put into place to ensure we can defend our homeland," said VanHerck, the retired general.

He said one challenge is there are many overlapping authorities at the federal level. The Federal Aviation Administration, Department of Homeland Security, Department of Energy, and Department of Defense all own a part of the problem, but they are reluctant to absorb the cost or work together, he said.

"I think we're just too slow," VanHerck said.

This story was produced by The American Homefront Project, a public media collaboration that reports on American military life and veterans.

Copyright 2025 American Homefront Project